Here's why everybody has an accent when in English. And here's why it's ok.

Para português, clique aqui

“Is it normal to still not sounding like a native speaker after having one for a teacher and after having lived in an English speaking country?”

The short answer is: “yes, it’s perfectly normal and extremely common. And no, it doesn’t mean there is something wrong with you or your teacher and it’s good you have an accent, because it means you have a whole background from your culture and life experiences with you. Erasing it would mean an important part of who you are would be discarded from your interaction with others.

Let’s see how accents work?

The way the brain interprets sounds

The picture below features a Cat of a baby’s brain. In the first situation, the baby was exposed exposed to speech sounds, i.e., words. In the second, to noise. This is a perfect example of how the brain works. As we come in contact with our first language we develop patterns on what has meaning and what doesn’t and we learn to react to them. That means if your brain has never been exposed to certain sounds, it won’t necessarily interpret it correctly (or at all).

2. Our patterns of which sounds have meaning and which ones don’t

Children’s brains are like a sponge, absorbing as many patterns as possible to learn how to cope and survive. Have you noticed how curious children tend to be? Or how they listen to a new language and pick up the accent so well? That’s because their patterns are being formed along side with their brains, so everything around them has potential to have meaning and to stimulate them. As we grow older, our patterns get more fixed and we tend to absorb new content less and less. That means as an adult you have probably had so many occasions being exposed to the same words, that your brain will dedicate much less attention to picking up new ones Wanna see how it works?

Check out this video in Chinese and try to identify the sounds they are saying:

Now try this one in Swedish:

If you’ve never studied Chinese most of what they are saying seems to be impossible to put into words, right? e In fact, Chinese can be quite a challenge for English speakers, as its sounds are really different and there are characteristics of the language, such as tone, which don’t exist for us. With Swedish, however the difference, some words are really similar to English, and even though we get lost in most what they say, we can still identify certain words. What’s really weird is it seems like you understand them almost, but then you don’t. Isn’t that amazing? That has to do with the fact that the sounds of these words are similar to what we know from English, so our brain interprets them as such, but can’t really conclude what meaning is behind them. In other words, your brain might actually not perceive a sound it has not been exposed to.

How our brains and vocal chords are intrinsically trained

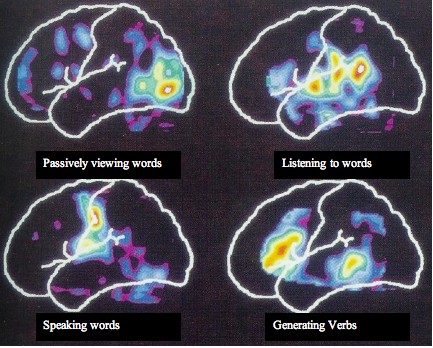

Below we have couple of interesting CAT scans:

We learn to listen and talk at the same time and with that our brains and facial muscles get trained in the same patterns; everything is connected. As we progress and learn to read and write, we also add meaning to written language, to what letters mean and what their combinations sound like. If English is your first language, for example, my name is a puzzle. Is it Luh-KAY-sis or Luh-TCHAY-sis? Well, guess what? It’s neither. Your phonological map, unless you have learned latin languages before, does not recognise the vowel in the middle syllable of my name. It’s the same sound of the é in fiancé and café, which to English speakers, by approximation, is an ay. Also, the ch sound is mostly pronounced as a -tch, but can also be a -k and much less often a -sh. It’s amazing how many ready-made patterns we bring to the classroom as adult learners and how it influences our perception of the new language as a whole. And it’s even more amazing how these influence what we actually hear and the way we say it.

The influence of out first language in our speech

The CAT scan below features brain activity for an adult speaking Spanish as a first language and the English as a second language:

A very interesting thing we notice is there is more brain activity when communicating in a second language, and some of that is in the same areas used for the first language. There you are. This is scientific proof the languages we speak influence each other and that adults need specific stimuli to learn how to perceive new sounds.In fact, our tendency with new languages is to approximate sounds as much as we can to our first language. If you hear a new sound as an adult, most of the time what your brain will do if compare it with the existing patterns and approximate. With that, what you hear a native speaker say might literally sound different from what they did.

An example of that is the word “Sri Lanka”:

In English, there aren’t any syllables that start with “sr” so our tendency is to hear shr, a sound that does exist in English. Therefore, it is perfectly normal to hear what native speakers say differently from what they actually did. So, yes, it is completely possible and plausible to have a heavy accent even after living abroad listening to native speaker pronunciation in class. You might actually hear it all wrong and being asked to repeat won’t necessarily make you improve it. Without the correct stimuli, the correct creation of patterns students won’t necessarily learn to identify new sounds or to produce them. Therefore, listening and repeating won’t necessarily make pronunciation perfect. An interesting point we often forget is speaking is a muscular exercise, and by that I mean speaking means you have trained you vocal cords, your lips and your tongue to produce a sound. If a sound is new, your body might not be trained to perfect perform it, just like in your first day at a Zumba class you might not get all the steps right. Therefore, you could live in an English speaking country, speak mostly with native speakers on a daily basis, have a native speaker for a teacher and still not pronounce things correctly. The key to improving pronunciation is finding what sounds in your language (or if you’re a teacher, in your students’ language) differ from English, and see what facial and listening exercises you need to do to get it right.

A practical example:

In the snippet below, I and my student are practicing -ed ending words. I start off by stimulating the student to try and think of words that would have that ending sound, which is a new thing to him. What I here is for him to be exposed to new sound combinations and to what look like in my face. After that, we move on to having a conversation about his last week, which will require him to use the verbs. Instead of telling him the sentences I want him to repeat, I ask him questions that will require them: